Benjamin Roche is a Research Director at the French National Institute for sustainable Development (IRD), where he is the “One Health” scientific advisor of the CEO, and a specialist in interactions between biodiversity and infectious diseases. Along with Marisa Peyre (CIRAD) and Jean-François Soussana (INRAE), he is one of the three coordinators of the international PREZODE (Preventing Zoonotic disease emergence) initiative, which was launched by these three institutes in January 2021. He talks about the One Health approach, COVID-19, the originality of PREZODE, and how researchers and innovators from African, Caribbean and Pacific countries can participate in the initiative.

Before talking about PREZODE, could you remind us in a few figures the share of infectious diseases – more particularly emerging diseases – of animal origin in humans?

Since the beginning of the 1980s, there has been a very sharp increase in the number of emerging infectious diseases. The first was HIV, then there were the first SARS, SARS coronavirus in China in 2003, MERS coronavirus in the 2010s in the Arabian Peninsula. We have had repeated avian flu crises, Zika, Chikungunya, dengue… Since the early 1980s, we have realised that the infectious diseases that used to affect human populations are tending to have less weight – although malaria still kills 500,000 people a year, and tuberculosis just as many – and that we have entered the era of the emergence of infectious diseases. And with an increasingly connected world, now when you have an outbreak somewhere in the world, it can turn into something global very quickly, which we saw with COVID 19: a few cases of SARS in China in December 2019 put almost the whole planet into lockdown just four months later. More than 75% of these emerging infectious diseases are zoonoses, in other words, pathogens that first circulate in animals and will tend to jump to humans and adapt to this new host, to be able to spread effectively to humans. Just to give you an idea, in terms of potential, it is estimated that today there are about 1,500,000 viruses that we don’t know about, of which between 500,000 and 800,000 can affect humans. And that’s for viruses, because there are also bacteria and parasites.

What are the main factors that can explain their multiplication in recent years? In particular, you have done a lot of work on the link between biodiversity and epidemics…

Yes, we realise that there are many factors linked to human activities, in particular the wildlife trade, deforestation and urbanisation, all of which impact on the functioning of ecosystems. In ecosystems, there are many microbes that circulate. And when these interaction networks are disrupted, they will re-establish themselves in a different way. For example, there is an effect that I have worked on quite a lot, which is the dilution effect. We realise that in fact, when we have a high level of biodiversity, i.e. a lot of species, we have some species that can transmit microbes and others that cannot. When we lose biodiversity, we will lose those species that cannot transmit them, which act as a brake on the transmission of microbes in ecosystems, and so by removing the brake, microbes are transmitted more easily in ecosystems. Furthermore, activities that impact biodiversity, such as deforestation or urbanisation, bring human populations increasingly into contact with animal populations, which are themselves increasingly infected. So, we have a perfect cocktail for the fact that there are more human populations exposed to these different pathogens and that there is an increase in the probability of the emergence of epidemics.

How has the COVID 19 pandemic highlighted the importance of a One Heath approach? And do you think there will be a before and after to COVID in this respect?

We hope so, yes, we think so. There are many things that have been launched on these One Health aspects. We also need to develop prevention strategies. Until now, we have had a very public health, human approach. We need to be better prepared when pathogens arrive in human populations. These aspects of preparation are of course very important, but often, what will emerge is something that we have not foreseen. So it is important to combine these aspects of control with aspects of preparation and aspects of prevention. To ensure that pathogens circulate less in ecosystems and/or that human populations are less and less in contact with these infected animal populations.

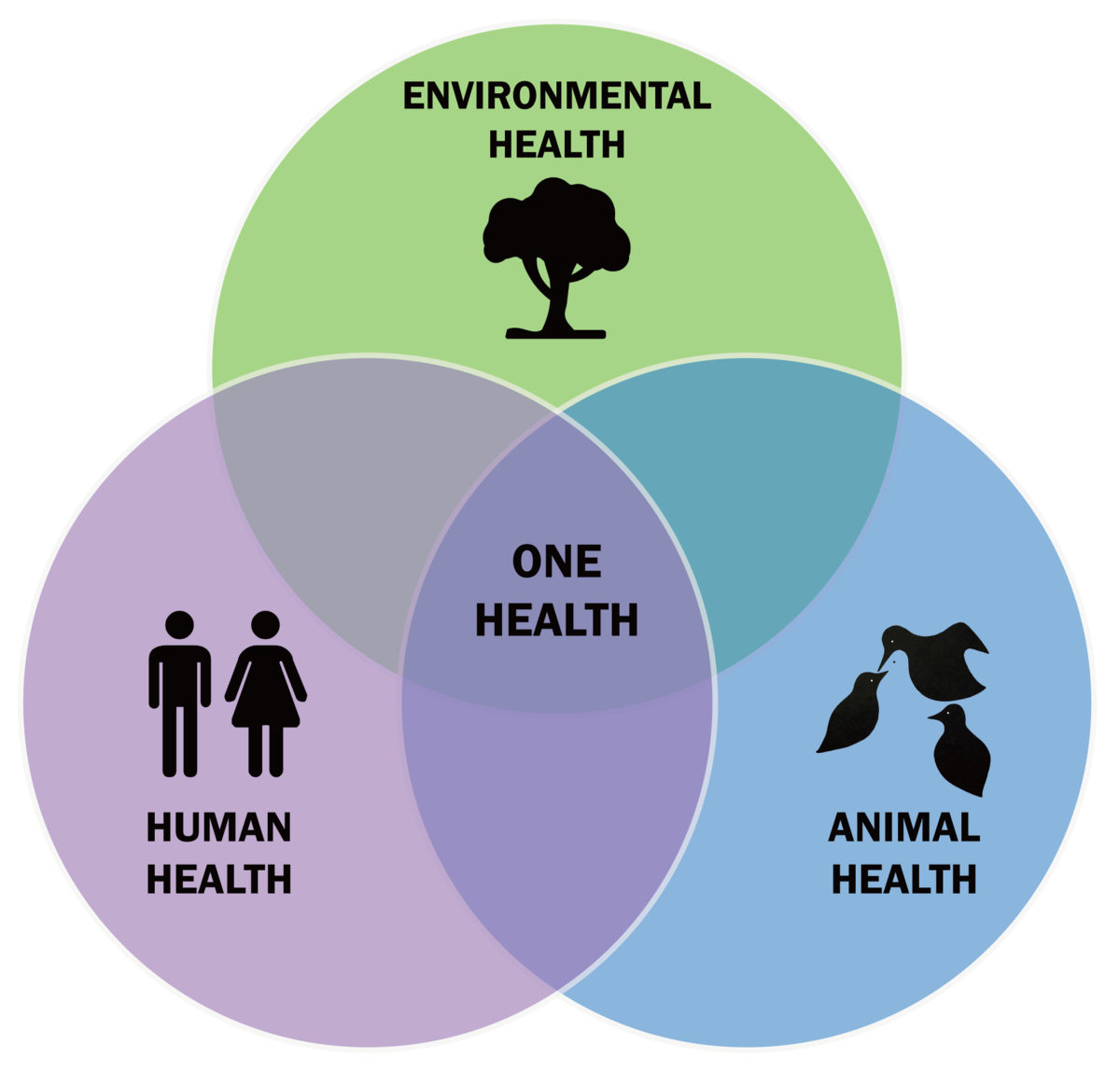

Could you remind us in a few words of the One Heath approach?

Initially, it was to connect human health and veterinary health. Then, little by little, other concepts emerged, Eco Health, Planetary Health, Global Health. Today, the term One Health is used more widely, and includes the fact that animal health is linked to environmental health, which is linked to human health and vice versa. So these three health areas are integrated and interact with each other; they must be considered as a whole and not just focus on humans.

There are quite a few initiatives today that are inspired by the One Health approach. How does the PREZODE initiative differ from other initiatives?

Firstly, on priorities. We are promoting the improvement of One Health surveillance networks, both domestic and wild fauna, which are often forgotten, and the human aspects. Improve surveillance at their interface, and develop prevention approaches. I think that PREZODE is the only one to do this: to understand how we can manage and design socio-ecosystems, with all their societal, socio-economic and cultural dimensions, which are more resilient to the emergence of zoonoses and which really enable us to reduce the exposure of human populations. These are the priorities. As for the approach, we have an initiative guided by science, which is important to emphasise because this is not always the case, and above all, it is an initiative of co-construction with all the stakeholders. For the past year, we have held co-construction workshops throughout the world, in 10 regions. We have brought together the various actors from different sectors – human health, animal health, environmental health, academic research, NGOs, authorities – to identify the problems, the knowledge gaps and how to solve these problems, to really co-construct the solutions with all the actors, starting from the local to the global level. This is the approach that characterises PREZODE and we are really the only ones to develop it.

What have you done since the launch of the initiative, what are your main achievements and the next steps planned?

PREZODE is an initiative that was launched by the French President at the One Planet Summit last year. Even though the initiative was launched by France, it is really an international initiative. And in the last year, seven governments have joined the initiative – Mexico, Belgium, Zimbabwe, Vietnam, Cambodia, Costa Rica, and France, of course. We also have over 90 health research institutes and NGOs that have signed the declaration of support for the initiative. And we have done these co-construction workshops. So we are really in an international initiative. France initiated the first funding of 60 million euros, which is not negligible. 30 million for academic research and 30 million for development aid through AFD projects. We are in the process of starting the first tranche of projects on this AFD budget. We have also made the initiative known internationally. We took part in the IUCN congress, the One Health Summit, the Africa-France summit, etc. We will of course continue to accelerate the internationalisation of the initiative. We will organise scientific workshops in a month’s time to refine the initiative’s research agenda. And with all this material, we will write a strategic research agenda that we will submit to the initiative’s interim governance, which is made up of the various institutes and signatory governments. Once this strategic agenda has been validated, it will be the initiative’s roadmap for the next 5 to 10 years. At the end of the year, we will enter the international governance of the initiative, where all the different countries will be able to participate in the funding and activities of the initiative.

How can researchers and innovators from African, Caribbean and Pacific countries participate in your initiative and at what levels?

They have already participated a lot in the co-construction workshops. All in all, over the 10 regions, we have had more than 1,000 people participate, from more than 50 countries, so normally they have already made their voices heard on these different research questions that we need to address. Then, as I said, it is an international initiative. So, we must also mobilise researchers and the various players so that their governments and institutes can participate in the PREZODE initiative: this can be via the scientific coordination of PREZODE by the various regional committees that will be set up almost everywhere in the world with interim governance. You have to be a signatory of the PREZODE initiative to participate, but it is not binding or committing, it is just an agreement in principle of interest. Afterwards, we are in discussion with various American and international, European donors. We will have to implement this PREZODE initiative in the various countries. And there, it will be the role of researchers and local actors, either to mobilise funding within their country, or to come and see the different funding that could be allocated to the PREZODE initiative to implement these different actions locally. Over the course of the year, the different institutes and signatory countries of the initiative will be kept informed. Public announcements will be made on the PREZODE website (www.prezode.org), and through traditional channels.

What are the main challenges for the PREZODE initiative to succeed?

There is always the question of funding. At the moment we have 60 million euros. Our objective this year is to reach 200 million euros for the next five years, with the various donors. Another crucial point is that this initiative is really taken up by the various players, the various researchers throughout the world. Some people are starting to call themselves ‘prezodians’, which we are pleased about. We can see that the originality of the initiative is well understood. All the international organisations have welcomed the initiative. Now, what is needed is for the different actors to appropriate it and for us to at least develop things on the ground, because that is really where it is going to be played out.

Last question, what links do you see between emerging diseases and climate change?

There are clearly some, but it depends on the disease. There are some fairly clear links, for example with malaria, cholera, diseases that involve the environment a lot. Afterwards, what is interesting is to see the interactions between all these global changes, the loss of biodiversity will accelerate climate change, which will accelerate the loss of biodiversity. Climate change and the emergence of infectious diseases are different manifestations, but of the same basic process, which is the impact of humans on ecosystems. We will not be able to combat pandemics if we do not combat climate change and vice versa. So interactions should be made between the different scientific and decision-making communities. The pandemic must be a wake-up call.