In the run-up to the second UN Ocean Conference, and a few days before an OACPS meeting in Ghana of ministers in charge of fisheries and aquaculture, we speak to Andrew Hudson about the central role of research and innovation in conserving and sustainably using the oceans, seas and marine resources for a thriving blue economy. A chemical oceanographer and marine resource economist by training, and current Head of UNDP Water and Ocean Governance Programme (WOGP), he oversees and provides strategic, policy and technical guidance on all aspects of the development, implementation and evaluation of UNDP’s work in water, freshwater and ocean governance, with a currently active portfolio of about US$400 million, working in over 100 countries (see text box on WOGP).

The upcoming U.N Ocean Conference will focus on scaling ocean action based on science and innovation to achieve SDG 14 and its 10 targets. What are the most pressing challenges that research and innovation should address today to ensure sustainable, resilient, healthy and productive oceans?

Each of the 10 SDG 14 targets has elements of that question. For example, the ocean acidification (14.3) is an issue with a very active research program, because it is a major threat. We know unequivocally that 30% of the CO2 we put into the atmosphere dissolves in the ocean, causing its acidification. Many organisms do not have the capacity to manage large changes in ocean acidity and especially at an extremely y rapid rate, which is what is occurring today. Therefore, there is a lot of research in this area, but definitely more is required to understand the specific impacts of ocean acidification at the species level and at the ecosystem level. How will it affect coral reef ecosystems, kelp ecosystems, ecosystems in the Arctic and Antarctic in particular, because it is even worse in the Antarctic, because like any gas, CO2 dissolves more quickly in colder water. Ocean acidification threatens, for example, the integrity of coral reefs, which fix their skeletons with calcium carbonate, and of course, the more the acidity goes up, the pH goes down, the bigger challenge that coral reefs have in making their skeletons, which is their whole basis.

The fisheries target (14.4) is a key one, plus the one on destructive fisheries subsidies (14.6) and the one on blue economy, SIDS and least developed countries (14.7). The good news is we have a good understanding of the fisheries challenge. We know overfishing affects about 35 percent of all the world’s stocks, we know the global fish catch of wild fish has been pretty much flat for 30 plus years (about 85-90 million metric tons per year). The percentage of stocks that are exploited unsustainably has continued to creep up, even since 2015 unfortunately. Therefore, there is a lot of work required there. You can’t manage what you do not measure, right? The more information we have on the very complex nature of how fish stocks behave, reproduce, feed and survive in general is, of course, critical input to setting things like upper limit targets on fishing, to inform fisheries management and fisheries enforcement agencies and organizations as to what are the appropriate levels to set and to enforce. One of the biggest challenges in fisheries is enforcement. Estimates are that around 20 billion dollars or so of the world’s gross fish value is caught illegally or unreported or unregulated. So that’s a huge issue. There again, knowledge, research on the nature and behavior of the fleets that are fishing illegally is very important. There’s a lot of really exciting initiatives happening, such as the Global Fishing Watch, which uses publicly broadcast Automatic Identification System (AIS) data to track tens of thousands of fishing vessels around the world, in order to detect illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing, helping fisheries managers better know and manage the fishing activity in their waters, as well as in international waters.

©FAO

OACPS ministers in charge of fisheries and aquaculture will gather next month in Ghana on the theme “OACPS Blue Economy Agenda 2030 – Catalyzing, the sustainable and agriculture development for the future”. How science can help policy-makers ensure a sustainable blue economy?

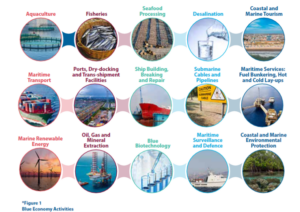

At UNDP, we thought hard about the concept of the blue economy a couple of years ago. It is of course about sustainable use of ocean resources and we framed it in terms of benefits, jobs, livelihoods, food security, economic development and poverty reduction. Within that, we touched on two key elements of the blue economy. The first is that many people do not realize that the current misuse of the ocean, if you add up the pollution and the overfishing and the invasive species, etc., costs humanity every year around a trillion dollars. Therefore, the blue economy has to be first about recovering that lost income. In many ways, our work at UNDP and in the broader UN system, for decades, even before the blue economy was a new idea, has focused on ocean restoration and protection towards recovering those socioeconomic losses. A significant amount of resources and investment has gone in that area and must continue. At the same time, there is clearly a sizeable funding gap to meet SDG 14 by 2030. The other exciting aspect of the Blue Economy is, what are the truly new and innovative ways to make money sustainably in the ocean? Things like ocean energy, marine genetic resources and aquaculture: there is a huge need for research and innovation in these areas area to get it right; for example, a lot of aquaculture isn’t very sustainable. Because there is no question, we need to continue to scale up aquaculture if we are going to feed the world – cultured aquatic protein now provides about half the aquatic protein that is consumed on earth, the other half being wild caught fish – but we need to do it sustainably. To promote new ocean related investment in their countries, governments need good research and data. UNDP is part of an exciting new initiative with a whole bunch of partners called the Global Fund for Coral Reefs (the only dedicated Fund to SDG 14) that is trying to support and catalyze reef positive investment. In other words, private sector investments that can both protect reefs and generate a profit. It is a big experiment. Now the question is ‘Can models be developed to come up with a concept that can apply to other ocean challenges’. It can be reef positive, kelp forest positive, mangrove positive. Can we find ways to both strengthen, preserve and protect or even enhance the ecosystems and make some money?

© UNESCO

What are the main obstacles to overcome in order to move quickly from science to action?

It is a big and important question. It is everything, from scientists having the willingness to speak about their work publicly, in relevant forums and conferences, its pertinence to the various ocean challenges,- which I think they are doing more now -, to the process of translating research to policy, which takes time and hard work communicating the science to the policy makers. Increasingly, with mechanisms like unrefereed preprints, research is publicly released even before it has been peer-reviewed. With that caveat, understanding it has to be peer-reviewed, but at least the knowledge is already out there for scientists and policymakers to look at and start to make informed decisions. Policy-makers, on the other hand, are not necessarily scientists, so they may need support in their own structures and institutions to interpret good science.

Could you tell us more about the UNDP Ocean Innovation Challenge, whose latest deadline for submission of proposals to its third call is 9 April 2022?

Shortly after the first UN Ocean Conference in 2017 in New York, we realized that the very ambitious SDG 14 targets – with four due in 2020 and one in 2025 – were not moving at the rate they needed to be achieved. So, in partnership with a couple of our key donor partners, Sweden and Norway, we came up with a new initiative called the Ocean Innovation Challenge. The idea is that by providing seed capital, support, mentoring and advice to innovators of all kinds (startups, NGOs, governments, academia, etc.), we can accelerate progress. We have done three successive annual Calls for Proposals, framed each time around one or several SDG 14 targets. The first one was on marine pollution, including plastics, but also nitrogen and other pollutants. It was amazing. We received 600 plus proposals in two months and finally selected eight projects, each project getting around two hundred and fifty thousand dollars. The second call was on sustainable ocean fisheries. Out of over 300 applications, we are just now finalizing the selection of around 10 to 12 projects for support. And the third call has been recently launched at the One Ocean Summit chaired by the French President Macron (Brest, France). This call relates to SDG targets 14.2-ecosystem based management of the ocean, 14.5 – marine protected areas, and 14.7 increase the economic benefits to small island developing states and least developed countries from the sustainable use of marine resources.

What are the most promising areas for researchers and innovators who want to engage in ocean related activities, according to you?

You know, the only reason the world has had the necessary amount of sea food and other aquatic protein to meet our food security needs over the last few decades is that while wild caught fisheries has not grown at all, aquaculture has made up the difference. So aquaculture, if you go back to like 1990, it has grown at a compounded rate at about six or seven percent per year. Today, pretty much half of all aquatic protein that humans consume on Earth is from aquaculture. In some projections, the World Bank predicts it will hit 60 percent by 2030. The good news of course is that it continues to help fill the gap in human food security while we take steps to get wild fisheries right. But like many things, not all aquaculture is sustainable. Some of it causes local pollution, from the fish excreta, waste of the fish processing, etc. . There is also an issue with cultured fishes, which have a very limited genetic pool, mixing with wild fishes and weakening the genetic pool of wild fishes. There is also the important issue of using integrated coastal management or marine spatial planning as a tool to help manage mixed demands (aquaculture, ocean energy, etc.) in coastal areas. It is a very active area of research to find models for sustainable aquaculture and mariculture. For example, UNDP supported work in the Yellow Sea, where they apply what is known as integrated multi trophic aquaculture (IMTA), an approach that moves away from single species culture, e.g. monoculture. It involves culture and harvesting of multiple species across different trophic levels, from fish down to the smaller and more basic organisms, clams, mussels, starfish, etc. In China and the Republic of Korea, they have been doing it for a long time. They get not only cultured organisms that they harvest, sell and consume, but they found that the water where they have these systems is very clean due to the fact that one species waste is another species food source. So they created a kind of simulated ecosystem model that has, for example, filtering capabilities, nitrogen absorption, and even a measurable positive amount of carbon that can be sequestered. These are the kinds of win/win innovations that can create sustainable supplies of seafood products while maintaining ocean and coastal health and productivity.

You have been also very vocal now for many years on ocean nitrogen pollution. Is it also an area where researchers and innovators should invest in more?

You see all the attention to plastics, which is merited because plastics is a huge issue. But for decades now, we have been drastically increasing the amount of nitrogen getting in the ocean; the total amount of anthropogenic nitrogen emissions to the ocean has roughly tripled since pre-industrial times. Nitrogen comes from two main sources. One is untreated or poorly treated wastewater. Only 20 percent or so of the world’s wastewater is treated at all. But, actually, the bigger portion, probably 90 percent at the global level, is from agricultural runoff of fertilizers in particular, as well as manure that’s not properly managed. Nitrogen and phosphorus are essential for ocean phytoplankton (microscopic plants) growth, but an overabundance of these nutrients is called eutrophication and can result in algal blooms. The bacterial consumption of this excessive algae growth then depletes the water of oxygen, causing hypoxia, with often dramatic consequences for fisheries, and coastal tourism. The cumulative effect is that over the last 30 years, we have seen a nearly exponential growth in the occurrence of coastal hypoxic areas, now numbering well over five hundred according to UNEP. So, there are big research needs there. What are optimal and cost effective ways to recapture and reuse nitrogen and phosphorus from both agriculture and wastewater? How could we reduce the runoff, loss of nitrogen and phosphorus in fertilizers? With things like creating buffer zones around farming land, using newer, slow release fertilizers that don’t get eliminated and washed off as easily, and even very precise injection technologies that bring fertilizers right to where it is needed in the plant. This is already an active area, but a lot more needs to be done, because it is one of the SDG targets where we have not seen major progress.

Key facts and figures

|

|

Indigenous peoples play a special role in ocean stewardship, care and understanding. How do you think Indigenous knowledge system could be successfully coordinated or utilized alongside Western scientific system?

There is a huge wealth of indigenous knowledge and experience going back thousands of years that should be increasingly tapped. Fisheries and aquaculture, which we touched on, is one example that the Chinese have been cultivating organisms for thousands of years. So there’s a huge experience there. Indigenous knowledge is vital and can be drawn upon. We have done a lot of work over the years with the Global Environment Facility (GEF) Small Grants Programme. We have provided grants of 25 to $50 000 to tens of thousands of community based organizations, NGOs, indigenous peoples organizations all around the world on ocean issues, but also on land issues, biodiversity, etc. There is a lot of experience there on small things that worked right and can be shared, replicated. It is a wide-open area.

2022, a year of unprecedented opportunities for transformational ocean action

|

|

Last question, Co-Chair of Friends of Ocean Action, Ambassador Peter Thomson, sees in this year unprecedented opportunities for transformational ocean action. A UN resolution has been recently adopted to develop a legally binding agreement on plastic pollution. Other pivotal meetings are planned in the coming months (see text box) where the international community could make significant progress. Are you optimistic?

I am mostly, but you know the conference itself is not the outcome, right? It is the things that all different stakeholders can announce and share during these conferences, whether it is launching a new initiative to sharing of best practices that others can build upon. It is the commitments that are made and then actually delivered that count the most. We are continuing what we started in 2017 with Peter Thomson’s strong urging at the time as the President of the UN General Assembly, the UN Ocean Conference registry. The 2017 Ocean Conference generated over 1,400 commitments across all the SDG 14 targets from a diverse range of global stakeholders, from governments to UN to NGOs to the private sector. This registry is still active and we are hoping to see another dramatic increase in the number of commitments made in the coming weeks. There will be an important political declaration, of course, coming out of the 3rd UN Ocean Conference, which is already being negotiated as we speak. Many UNDP side events will be held to highlight our work, share our experience. UNDP will spotlight the winners of the second Ocean Innovation Challenge on sustainable fisheries and I’m sure many other organizations will make other important announcements and contributions. But the real hard work I would say continues right after the conference – doing what you said you are going to do.

UNDP Water and Ocean Governance Programme

| The UNDP Water and Ocean Governance Programme (WOGP) helps countries achieve integrated, climate-resilient, sustainable and equitable management of water, freshwater and marine resources Ranging from a very local level with communities, NGOs and CBOs up through provincial, national, regional and in many cases, global level, WOGP focuses a lot on transboundary or shared freshwater and marine systems, including large scale shared river basins and large marine ecosystems. And within the framework of sustainable marine ecosystem management, they look at, among other issues, fisheries. For example, their about 20 years of cooperation and support to the Secretariat of the Pacific Community, the Pacific Islands Forum Fisheries Agency and the governments of all the Pacific island countries contributed |  |

to bringing tuna stocks to 100 percent sustainability, a first for the largest tuna fishery in the world (about 60 percent of the world’s tunas). They have also worked over the years with the UN International Maritime Organization –IMO- and the shipping industry on ships’ ballast water and hull fouling, to address both the issue of invasive aquatic species (one of the greatest threats to the world’s oceans), and climate change mitigation (as a ship fouled with organisms creates more friction in the water and burns 25 to 30 % more fuel, meaning more carbon dioxide emissions, than a clean ship). The GEF-UNDP IMO GloBallast Programme has notably contributed to the adoption of the Ballast Water Management Convention, which came into force in 2017. |