Salome Bukachi is an associate professor in the Institute of Anthropology, Gender and African Studies at the University of Nairobi in Kenya. She has a background in anthropology specializing in medical anthropology, with over 30 years of experience in research in Africa, looking notably at issues of health, livestock, nutrition and water. All of these issues are impacted by climate change. We talk with her about climate change and health issues in Africa.

Could you remind us of the major threats posed by climate change to health in Africa?

Climate change comes with a lot of issues that are also interconnected, and one of them relates to aspects of changing weather patterns. So you ever find too much rain which could lead to floods. And that also relates to waterborne diseases and diseases that can occur as a result of pathogens or vectors that find a lot of flood water conducive for their development, like mosquito breeding sites. We talk here of diseases such as malaria, and Rift Valley fever, among others. On the other side, there is the aspect of drought, extended periods of dry seasons where there is not enough rainfall. A lot of the agriculture in Africa depends on rain-fed agriculture. This has an impact on food production, and food security. Climate change also has an impact on health because, with reduced food, there is also reduced immunity. Another aspect is in relation to emerging diseases as a result of climate change, where we find pathogens are also kind of mutating. Extreme weather conditions are providing conducive environments for an increase in the number of vectors that spread disease leading to possible disease outbreaks. Water is very critical when you talk about health. And when you have drought, access to water becomes a challenge and people have to walk for several kilometers to be able to get water. Many times that water is not safe and healthy for drinking or for general consumption and use.

What solutions can research and innovations provide to make health systems more efficient, inclusive, climate resilient and sustainable?

One of the key challenges that health systems face is the inadequate supply of essential drugs and the inadequate supply of essential equipment that are required to address the health situations that communities face. Research can come up with technologies that can be used in resource-deficient areas, and digital technologies that can be used for diagnosis in such settings. Research can come up with innovative diagnostic kits or innovative equipment and tools that can be used to diagnose disease, even in rural areas with inadequate facilities in terms of electricity, running water, steady internet connectivity, and adequate staff. Finding ways of making solar affordable in such kind of places may also help. And also contributing to strengthening the local community health workers as well as coming up with homegrown solutions to meet the local health demands.

What role policymakers should play in accelerating the necessary transition to a more efficient, inclusive, resilient and sustainable health systems? What are the major obstacles to overcome to move more quickly from science to action?

Research has already provided empirical evidence that can be used by policymakers to improve and make the services more efficient. So, I think policymakers need to work hand in hand with the scientists, as well as scientists need to provide information in a very clear and simple way that can be consumed by the policymakers.

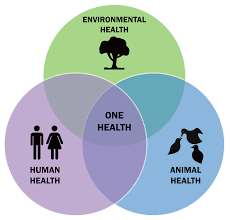

Why is it so important to link human health with animal health and environmental health in what we call the One Health approach if we want to make our climate change adaptation strategies more effective?

Human beings do not live in a vacuum. They operate in an environment and have very close interactions with their environment. And within that environment, we also find them living very closely with their livestock and wildlife too. Therefore, when we are looking at aspects of disease occurrence, because of this close relationship between these three components, the environment, the human, and the animal, it’s important that we look at issues from a One Health approach because all of them are interrelated. Emerging pandemics have a high correlation between these three aspects hence an impact on our environment triggers impacts on the health of humans and animals. If we just handle human health without dealing with animal health or environmental health, we miss out on providing holistic solutions that can be more sustainable and reach even marginalised communities. When we look at the environment, we find indigenous communities who have coexisted with their environments in a very harmonious way. We can learn about how they have coexisted with the environment, have used indigenous technical knowledge to conserve the environment and live in harmonious co-existence with animals.

The COHESA Project, which is being coordinated in Eastern and Southern Africa by the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), and supported by the ACP Innovation Fund, aims to strengthen the operational capacities of a wide array of public and private One Health stakeholders to prevent and cope with emerging health and environmental risks. What is the added value of such a project in your region?

I would say that it provides impetus to already existing initiatives. It builds upon what already has been existing on the ground, giving more concerted focus in terms of building capacity, and building competencies in conducting One Health research or training of One Health. It will also help strengthen policymakers to make relevant One Health policies and strategies. The COHESA project will leverage what is happening and work together with the already existing initiatives to strengthen the research, practice, implementation and training of One Health in Kenya.

What is your role in this project, as a local multiplier?

My role is about linking with the various players in the One Health space, bringing them together, given that I’m currently at the University of Nairobi and in the social science space. I contribute to bringing people of different disciplines together, from the environment, human health, veterinary health, ministries, all the relevant players, ensuring that we are working in a cohesive manner to provide solutions and improve One Health in Kenya.

You said once that human is core in the prevention, response management and control of diseases, hence it is critical to integrate social science in the one health approach. Could you elaborate further please on this?

Human beings are at the center of disease occurrence and disease prevention because they are the ones who interact with animals and ecosystems. Their practices can expose them to disease or help protect them. If we look at examples of pandemics we have had in the in the recent past, such as Ebola, or COVID-19, there were aspects that required us as humans to be able to take some measures to help protect us or protect others around us. Without us doing that, the disease would have spread. When we develop policies even at a global level, we need to work with the people on the ground to co-develop or co-create interventions that are appropriate, culturally, socially, economically and politically to their environments and contexts.